Prison Labor

The Great Depression and the 1930’s in general were a decade of change for Michigan prisons. The advent of civil service rules ended the patronage system for wardens, an attempt to combat political influence in prison administration. The Hawes-Cooper Act prohibited the sale of prison-made products in interstate commerce after manufacturers, employers, and labor leaders in the open market argued that they could not compete with prison manufacturers whose free labor force could not strike while labor unions in the open market could. The Michigan legislature adopted a bill limiting the sale of prison products to state institutions and tax-supported agencies.

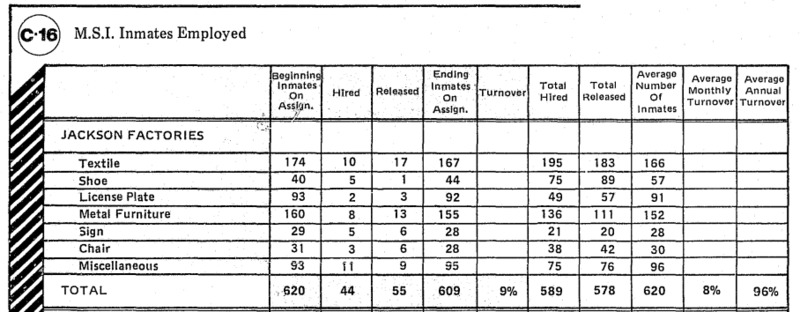

Heightened restrictions on markets for prison goods continued into the late twentieth century when Michigan State Industries, which used prison labor, were only allowed to sell their products to state institutions and tax-supported agencies. This excluded the sale of hobby craft, arguably the largest industry for inmates in Jackson, in which incarcerated persons, either self-taught or taught by other inmates, made products like earrings, paintings, chests, chairs, purses, wallets, and belts for up to $150 each. Inmates were able to spend $100 a month on supplies. They kept 90% of earnings with the other 10% going to the prison. Hobby craft as an industry exploded in the late twentieth century when more than 60,000 customers purchased $95,000 worth of goods. In 1971, a Hobby Craft sales store opened to meet surging demand. The store began to sell products nationally in the 1970’s. Inmates who participated in the program also volunteered their time and some of their earnings to make hundreds of toys for less fortunate children of the Jackson community.

Hobby craft was yet another rendition of prison employment, whose roots are intertwined with the expansion of prison systems throughout the nation and particularly in Michigan. In the nineteenth century and the early years of prison employment, powerful politicians in Michigan wanted to be able to use the burgeoning prison system to make money to pay for more prisons and fill the pockets of politicians themselves. This foreshadowed the way for further practices and expanding industries that employed cheap prison labor to turn a profit. Buoyed by a nationwide belief that idleness in prisons would be detrimental to the security of the prison as well as detrimental to the prisoners themselves, prison labor was seen as a way to solve these twin issues and produce a profit for prisons and the politicians that supported them.

Systems of patronage were set up between prisons in Michigan and the outside world with political connections granting outside business owners access to cheap prison labor in return for payoffs to prison management. In 1907 these practices were codified with an amendment added to Michigan’s constitution which allowed industries to use prison facilities as factories, and renting out the prison labor force and paying them substantially lower wages than the private sector, in return for supplying the machinery and raw materials.

Two of the early industries that specifically Jackson inmates were “employed” in was institutional construction, in creating the materials used to expand prison facilities further, followed by the roadbuilding. With the exploding automotive industry in Detroit, roads and infrastructure were at the utmost priority for Michigan. By 1924, Michigan had completed more miles of roads than any other state under the federal aid program. The reason that they were able to accomplish such a feat was because Michigan was heavily “employing” prison labor forces and paying them ⅕ of the normal labor cost. Road building was not the only industry that felt the impact of prison labor; throughout the 1920’s-1930’s, Michigan as a state was allowed to bid alongside private contractors for infrastructure and other federal aid ventures. Although low labor costs allowed Michigan to underbid many contractors from the private sector, the influence of business owners was mutually beneficial in certain senses as they were provided with a cheap labor force in the form of inmates if they conducted their work within prison facilities.

Governor Grosebeck (1920-1927) even appointed a prison commission, made up of many influential business owners in the state, to oversee SPSM. These appointees were able to serve their own interest by using prison labor for their own companies while also ensuring that Governor Grosebeck secured crucial political alliances to ensure his reelection. The obvious influence of political corruption and economic extortion in the use of prison labor in Jackson and throughout Michigan is a long lasting legacy of the prison system as a whole throughout the state and especially in Jackson.

Sources:

http://projects.leadr.msu.edu/statesofincarcerationmi/exhibits/show/dailylife/employment --> not availble anymore?

Corrections Commission. Michigan Department of Corrections 1980 Statistical Presentation. Michigan Department of Corrections, 1981.

Ostrander, Steve. "Prison Labor in Michigan." Michiganology. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://michiganology.org/stories/prison-labor-in-michigan/.

Smith, Leanne. "Peek Through Time: Prison's Hobbycraft Sales Shop turned idel inmates into skilled craftsmen." MLive. Published April 23, 2014. https://www.mlive.com/news/jackson/2014/04/peek_through_time_prisons_hobb.html.