Political

In some regard, all art produced under incarceration can be said to be political, in that mass incarceration is a highly contested and politicized subject in the United States and the constraints that it imposes upon those directly impacted permeate all aspects of their lives, including their creative endeavors. There are certain subjects represented by imprisoned artists, however, that are more overtly political, and prominent among these are images about incarceration itself.

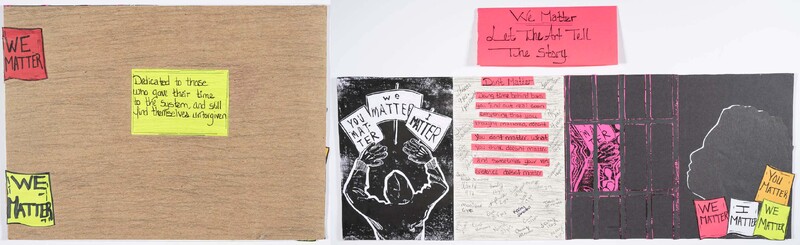

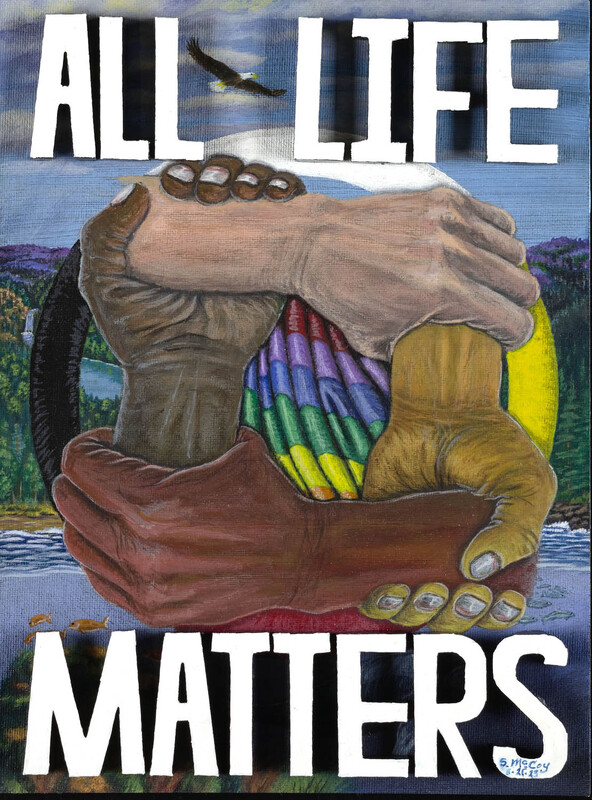

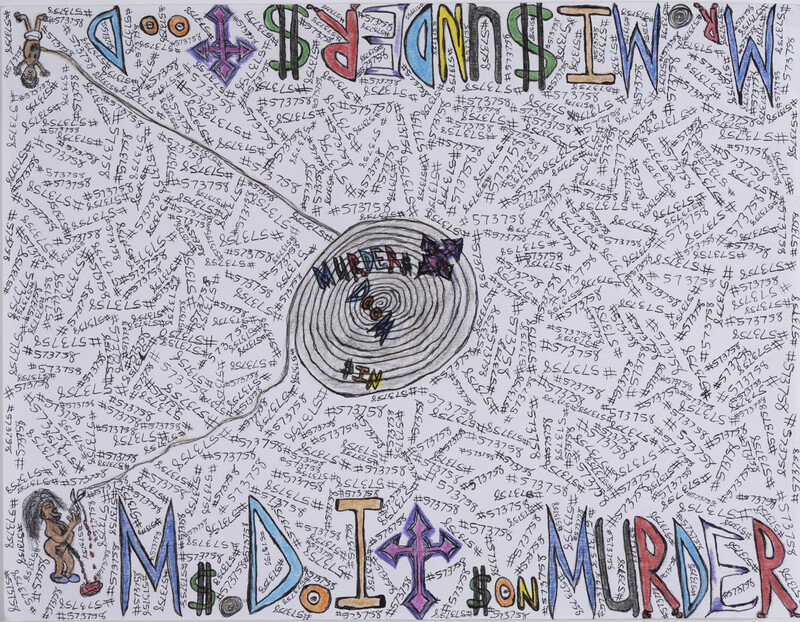

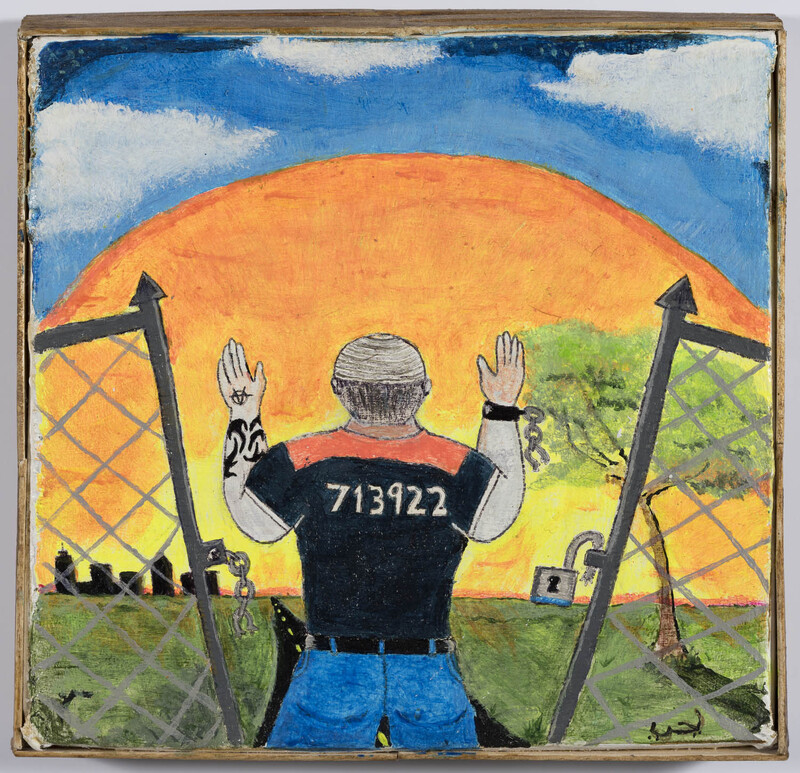

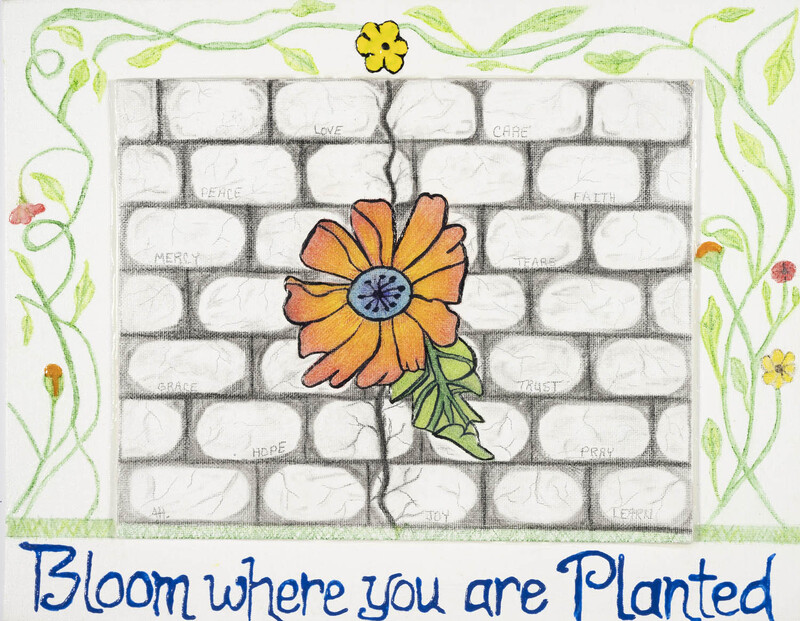

The literal telltale signs of prison imagery — bars, razor wire, ID numbers, the Michigan Department of Corrections blue uniforms with the orange stripe — can evoke the vulnerability, oppressiveness, isolation, and dehumanizing experiences of being unfree. This imagery can be counterposed by assertions of resilience, self-value and “mattering,” connectivity, creative envisioning, forms of freedom and futurity, and the right of self-representation. A metaphorical language speaks both eloquently and harshly of wrongful imprisonment and a pervasive miscarriage of justice. The bold lettering on a crocheted handbag articulates hope that “Good Time” legislation will pass in the Michigan state government allowing for early release. These representations are constrained by the limitations imposed on reportage and critique coming from inside carceral facilities.

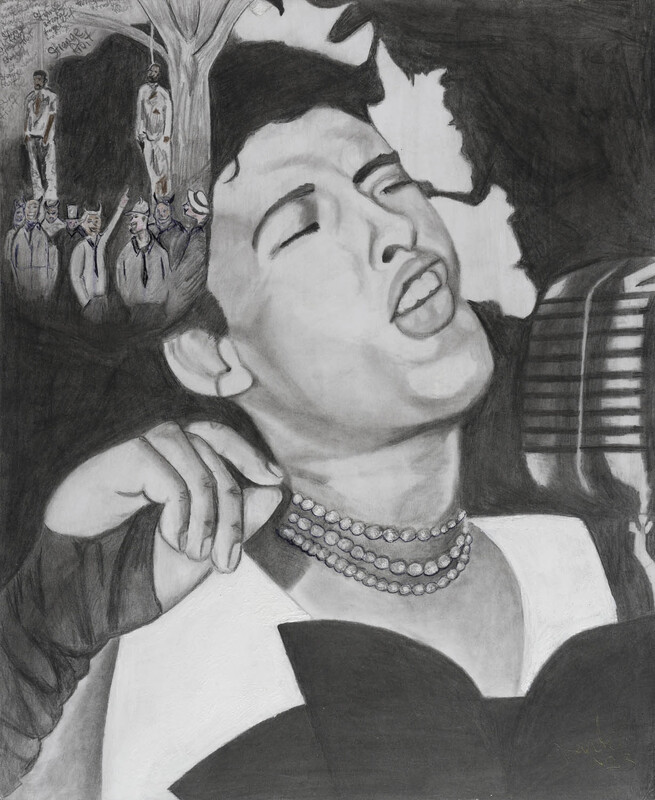

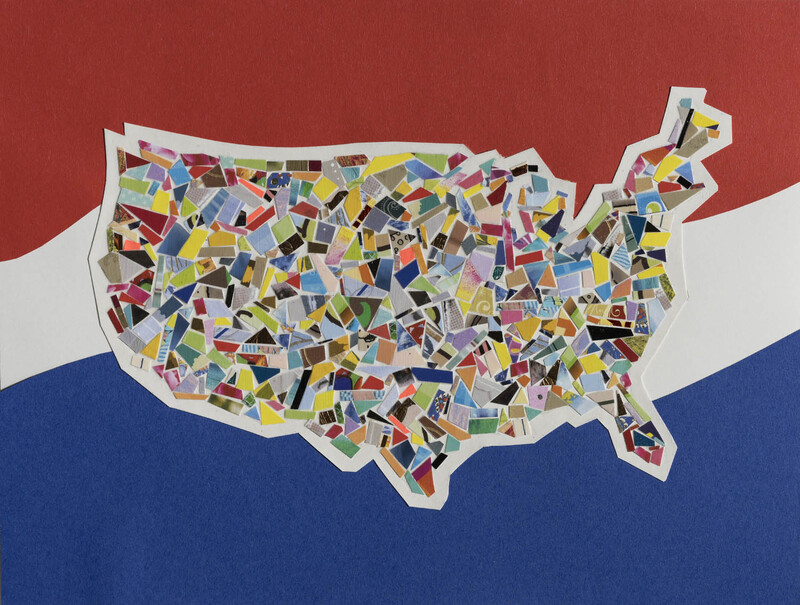

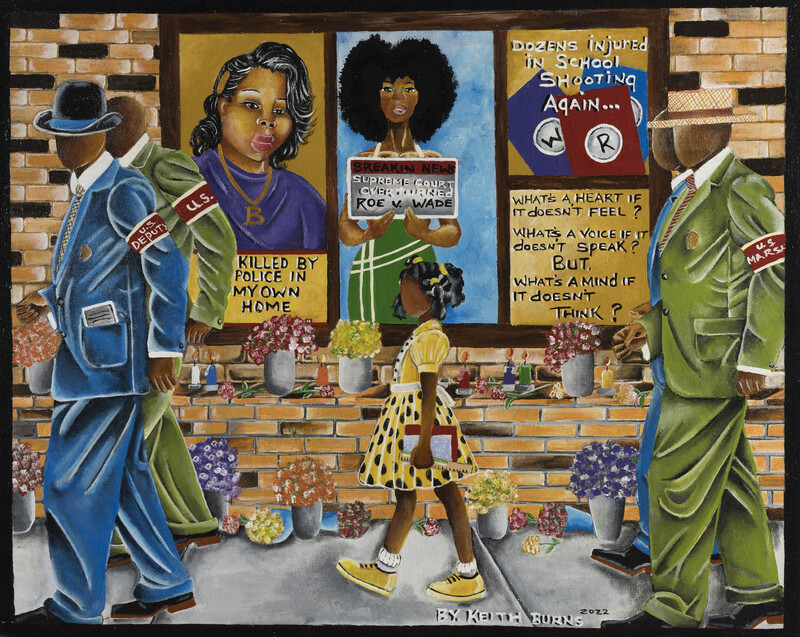

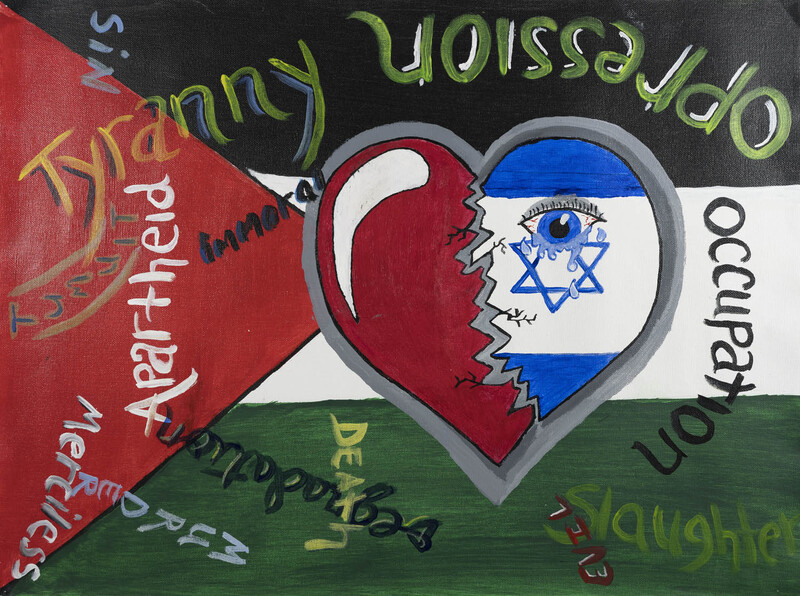

Prisons are also the place from which the incarcerated look out upon the world and respond to current events, changes within society, and global politics. There is commentary here on systemic racism and police violence, reproductive rights, LGBTQ+ discrimination, Indigenous histories, the war in Gaza, the U.S. presidential race and polarized politics, climate change and species collapse, school shootings, and the opioid epidemic, among other topics. These issues are often deeply personal, tied to identity and community, histories of trauma and dispossession, an empathy with the suffering of others, and an abiding concern about the future. The familiar anxiety triggered by the current global polycrises can take on a different aspect when visualized by incarcerated artists, registering, on the one hand, a more intense despair and lack of hope, and on the other, a necessary recourse to fundamental humane values like love, compassion, and trust, and a more radical fugitivity.

By: Megan Holmes