Prison as Art Studio

Environment

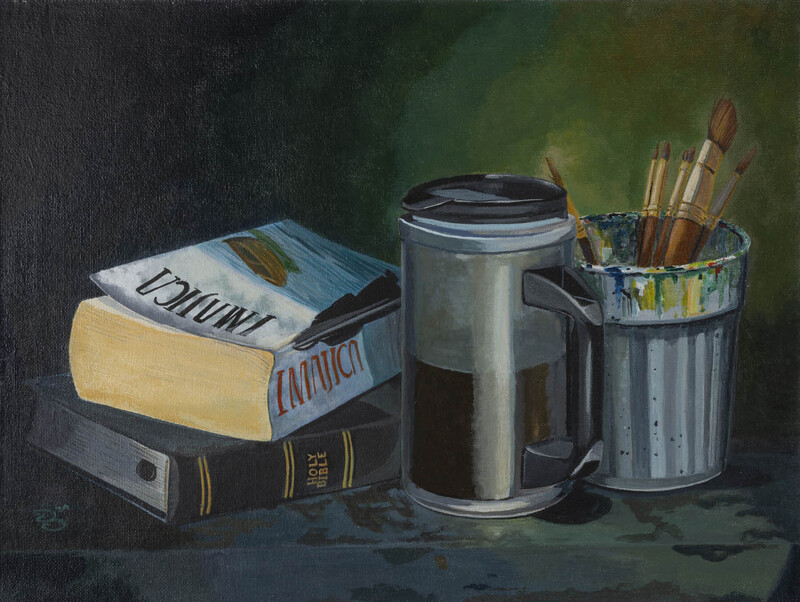

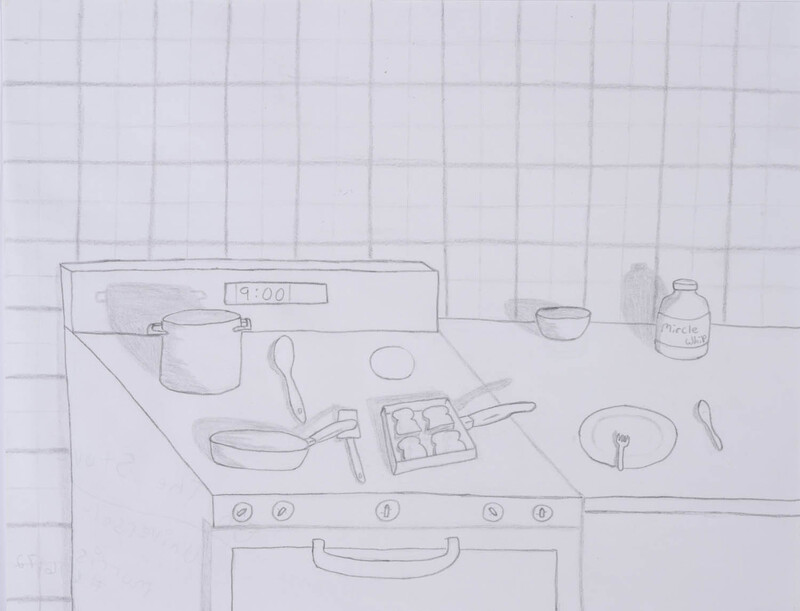

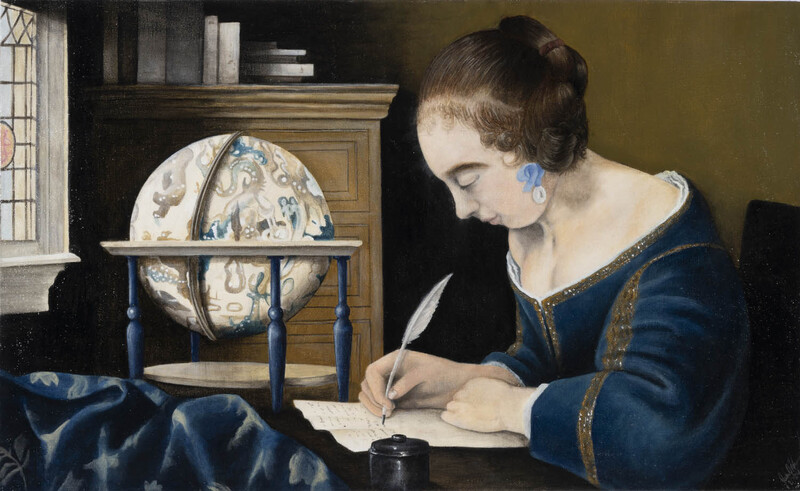

In Everyday Life by Don Schneider, objects sit casually on a shallow ledge—a paperback Clive Barker novel atop a Bible, a mug half-full of black coffee, a pigment-splattered cup holding five paint brushes of different sizes. Reminiscent of 17th-century Dutch still life painting, the picture deploys clever illusionism to explore the reflectivity and transparency of the surface of the drinking vessel. This plastic lidded cup, however, is a familiar item of everyday use inside prisons, purchased at the commissary. The presence of this commissary merchandise subtly communicates that the act of painting and the engagement with artistic tradition referenced in Everyday Life took place within a prison, where the prison itself operates as a kind of art studio.

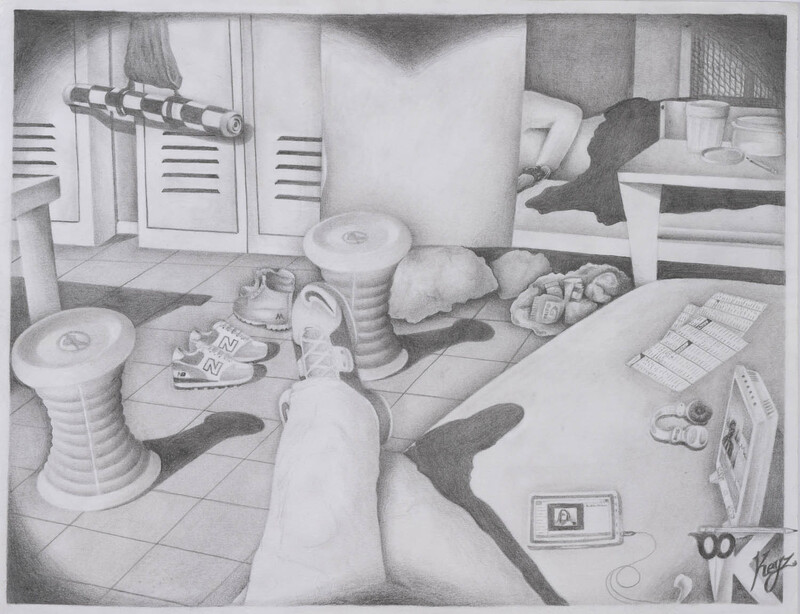

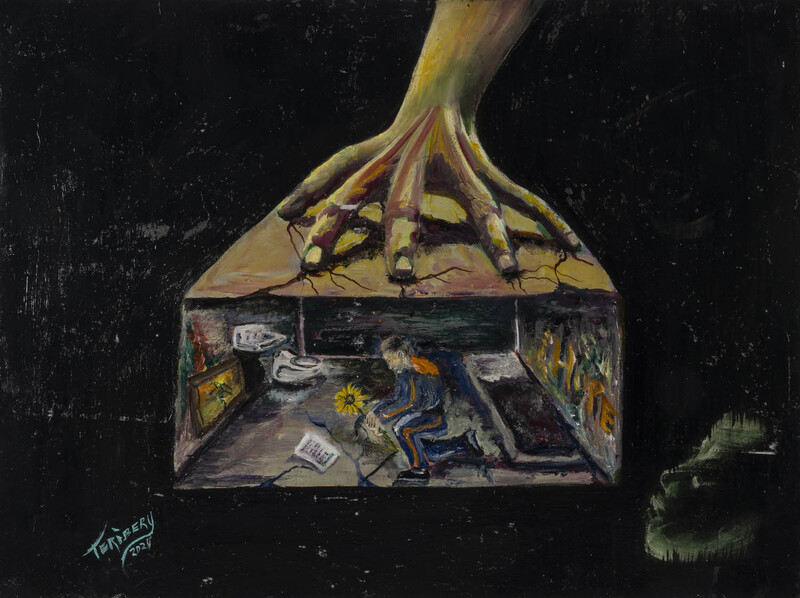

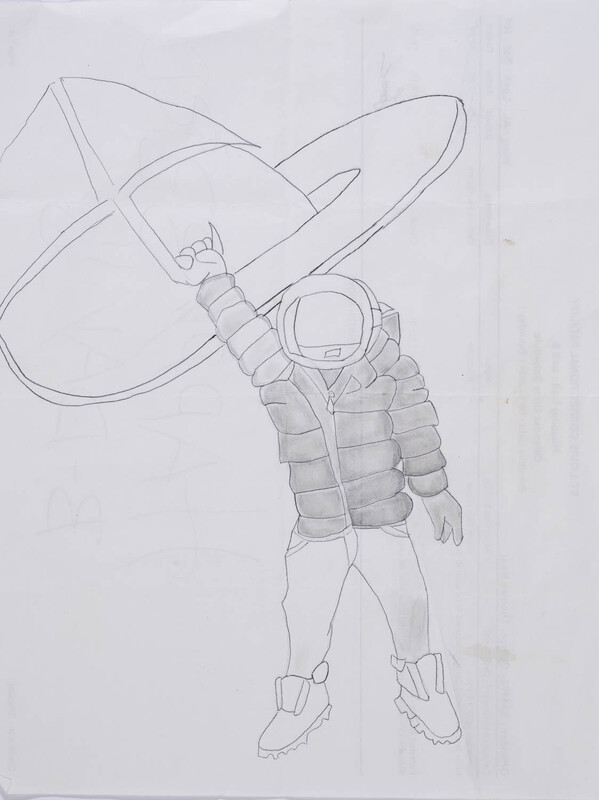

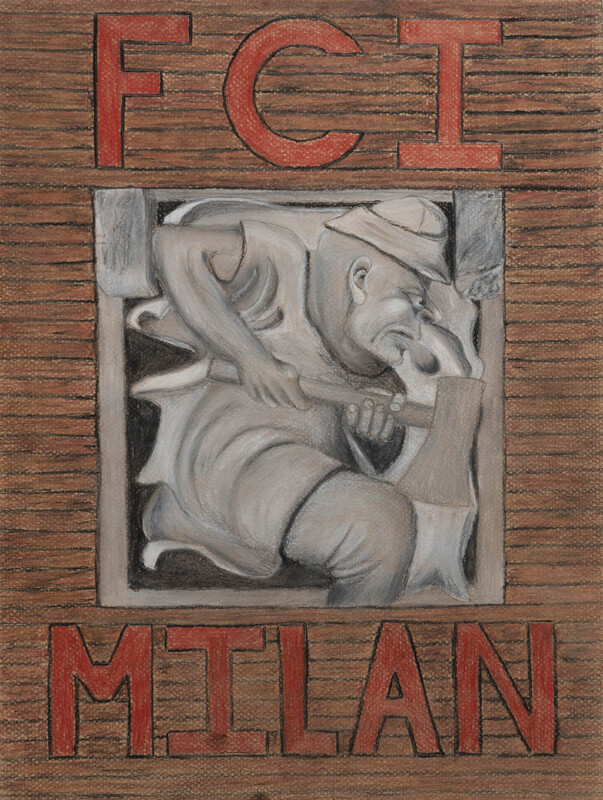

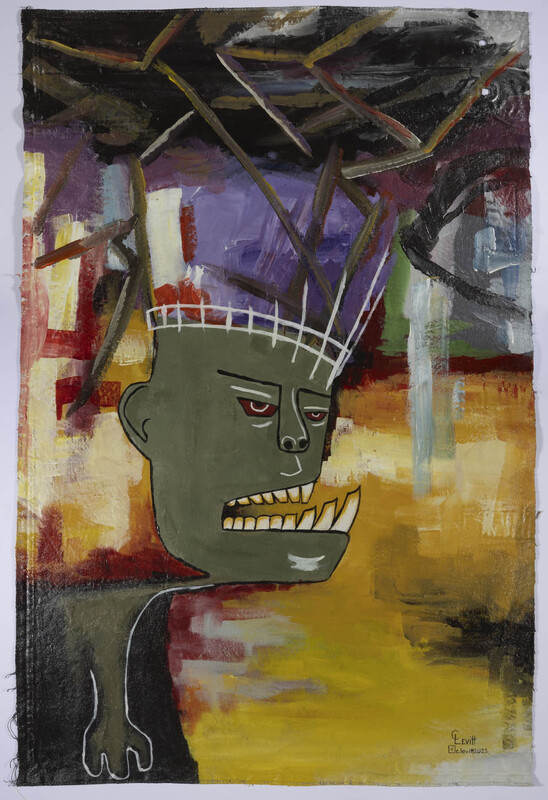

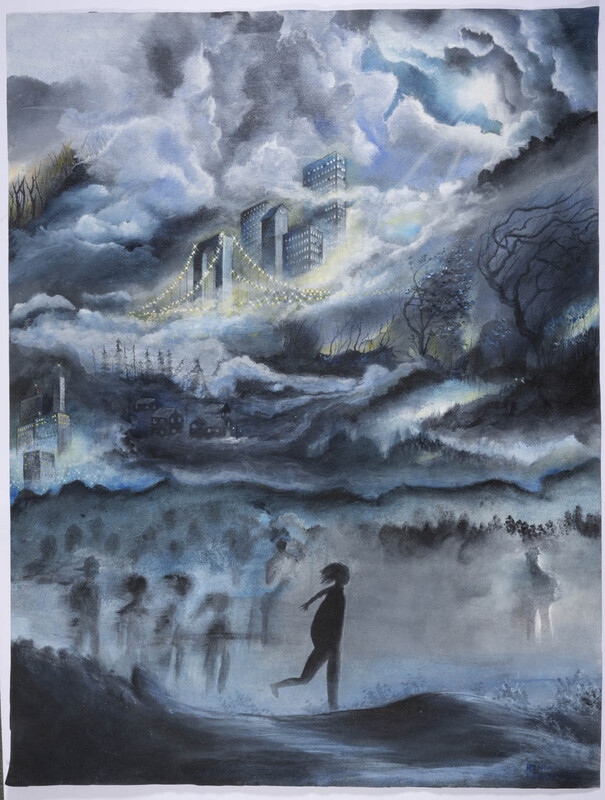

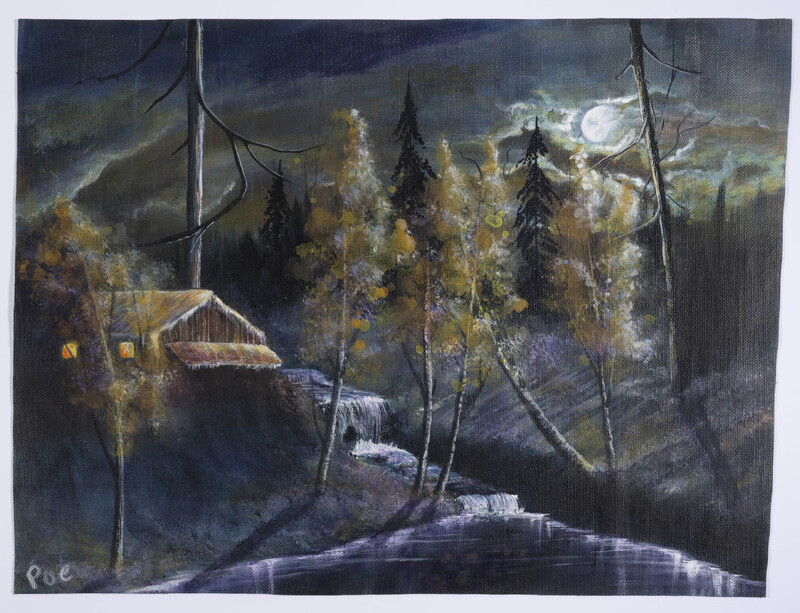

It will come as a surprise to many that prisons are one of the most active sites of art production in the US, given the scale of mass incarceration and the prevalence of art making practices within. This art production is fractured and dispersed across the physical spaces of the prison. It takes place in the cramped bunks to which many artists retreat to block out turmoil and disturbing sociality. Artists work in more communal settings in the day and rec rooms and in hobby craft classrooms, but also in the enforced isolation of segregation cells of approximately 70 square feet. D’von White was in segregation when he made his first artwork, Slow Process—a spare line drawing in pencil executed with a manual dexterity perhaps translating from his training as a welder, depicting a figure in an improvised space suit being airlifted the heck out. The art studio is represented literally in Keyz’s Photographic Memory, where we see the artist’s perspective looking out upon his housing unit, and more figuratively in Daniel Teribery’s subterranean nightmarish rendering of a creative space of survival in Hold On.

By: Megan Holmes

Creative Community

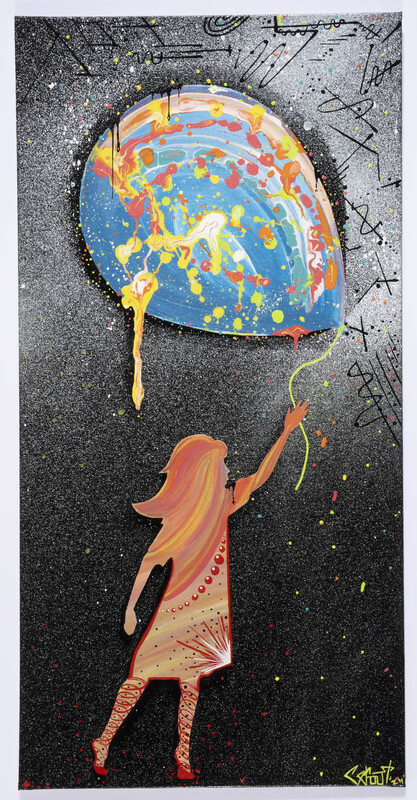

Prison removes individuals from their communities, damaging and even severing their connections with others. The rigidity of carceral life as well as the constant rules and surveillance function to stifle creativity. Under these conditions, it can be difficult to imagine how incarcerated artists are able to continue their practice. But there exists a robust creative community inside. Artists and other creatives consistently support and learn from one another, so much so that it is often reflected in their work. This creative community does not flourish because of prison, but rather in spite of it.

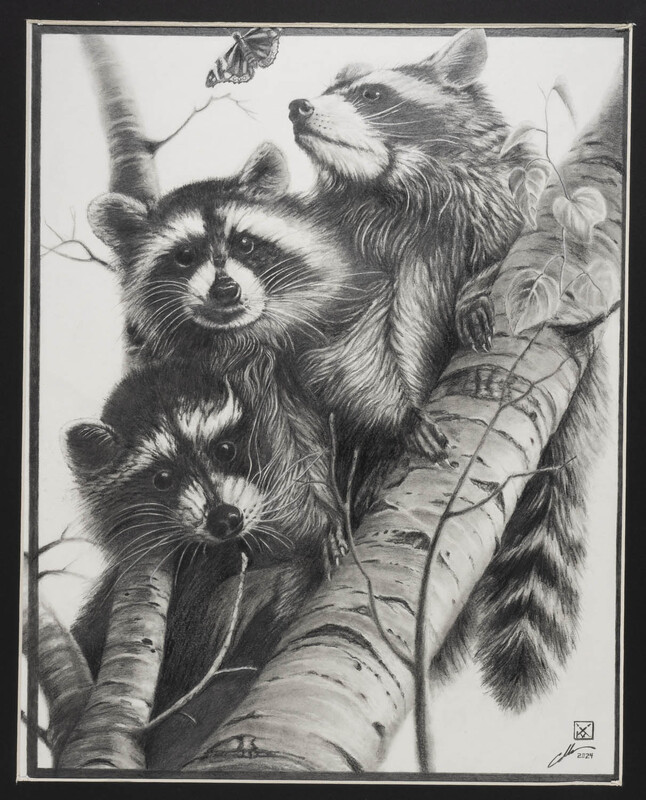

Mentorship and shared creativity happens in both formal and informal ways. Some facilities allow artists inside to teach weekly art classes to other incarcerated people, providing a dedicated time and space for artists to learn and experiment. Doc Collison’s piece The Charcoal Wash Bears w/ Mat Frame was born out of a challenge from his students. They questioned whether he could draw as well as he could paint, and the trio of charcoal raccoons served as his response.

But even without a class, incarcerated artists find ways to connect with each other, sharing materials, techniques, and ideas that often inspire pieces in the exhibition. Nino Tanzini and his bunkie William “Cowboy” Wright both have several pieces in the show. As Nino encouraged Cowboy to delve into art, their artistic practice grew. Their shared space–cell number 230– became Studio 230, an art collective. In Cowboy’s piece M.C.F. Friendly Squirrels, Nino is depicted walking through the yard in the background.

The creative communities that exist inside challenge the carceral logics that sustain prison. They reflect art’s capacity for building connection and encourage us to consider creativity as a site of resistance. Whether it’s a weekly art class or two friends sharing ideas, creativity thrives in community, and prison is no exception.

By: Suzy Moffat

Artistic Practice

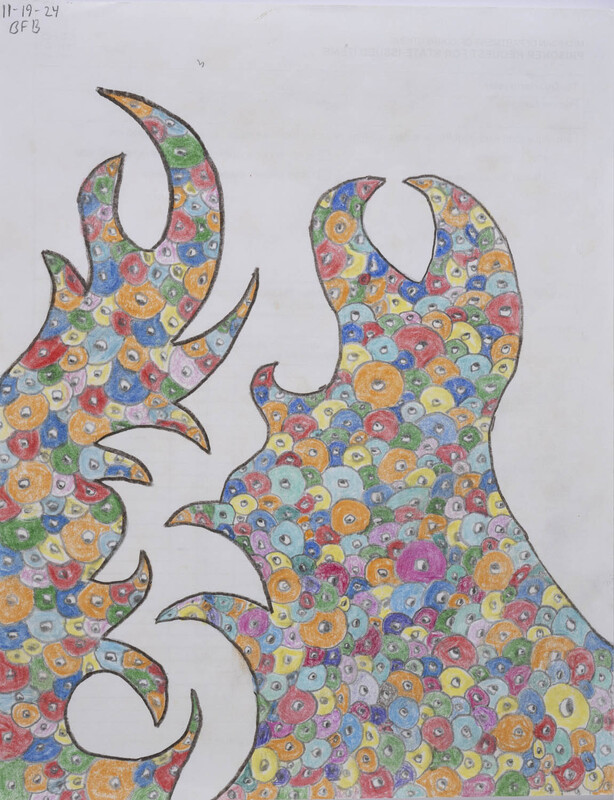

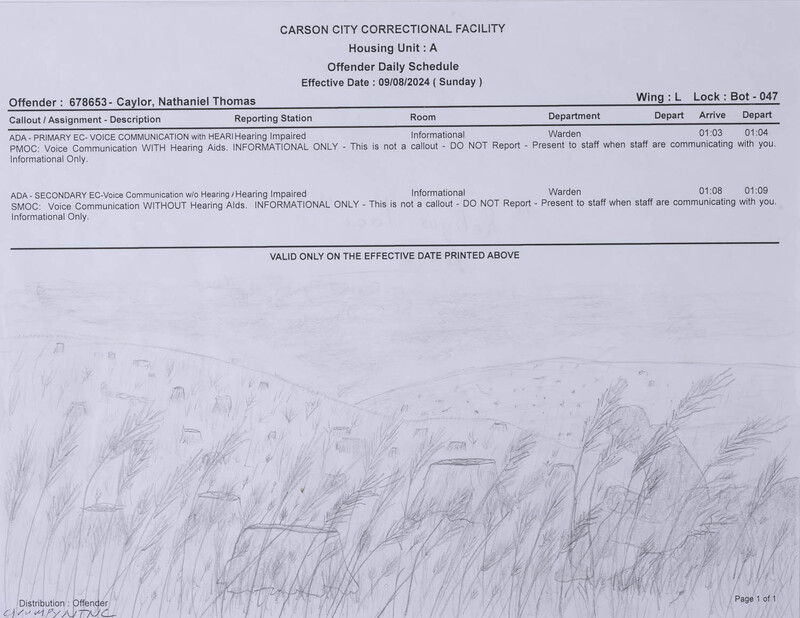

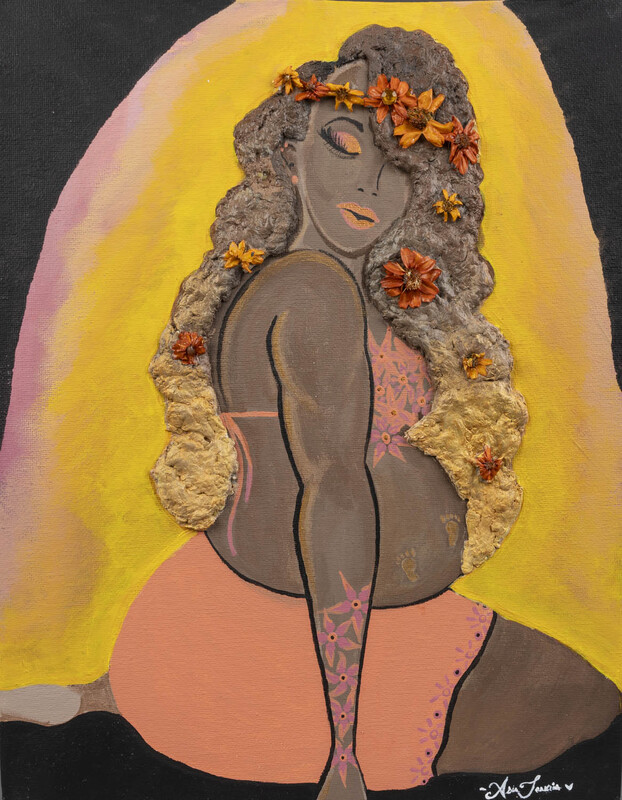

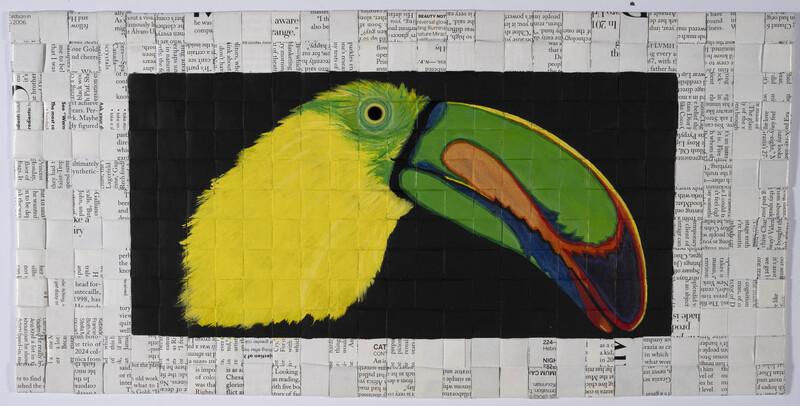

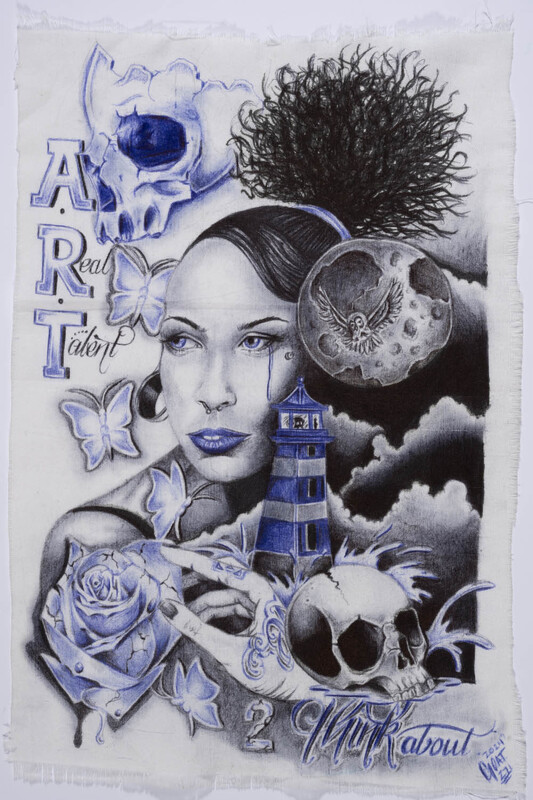

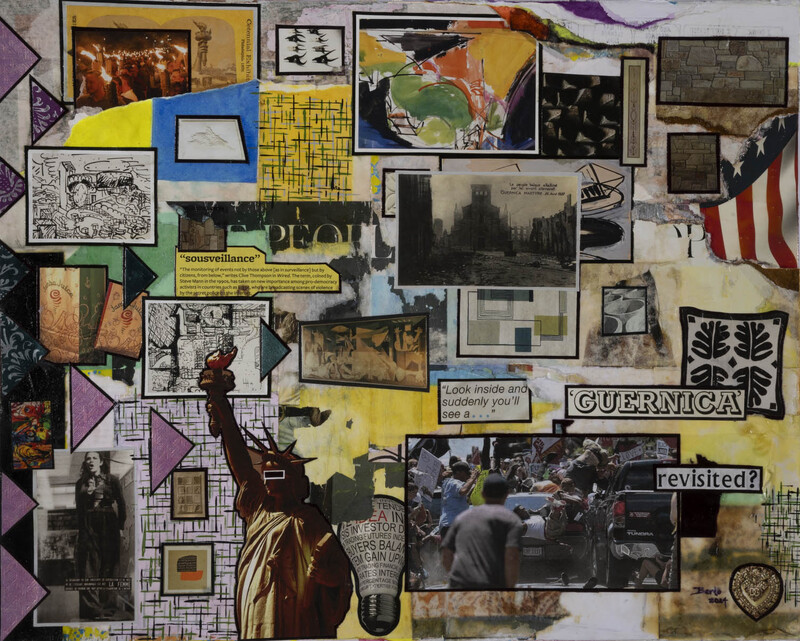

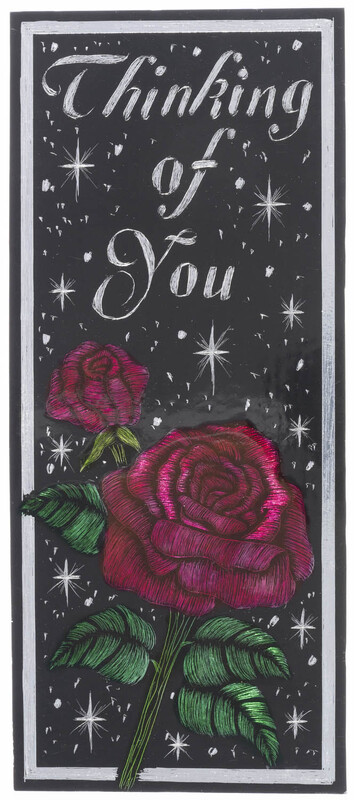

Art created inside prisons participates in multiple economies of art use and circulation, produced under conditions of material scarcity. Art materials are limited by prison restrictions and by cost and are vulnerable to theft, but they are also generously shared and gifted among artists. Artistic techniques, too, are passed on, often involving innovative ways of countering this material scarcity—novel forms of canvas; drawing paper repurposed from printed prison forms; a colorful palette extracted from coffee, M&Ms, Kool-Aid, and dye leached from colored paper; sculptural armatures made of cardboard and glue-saturated toilet-paper.

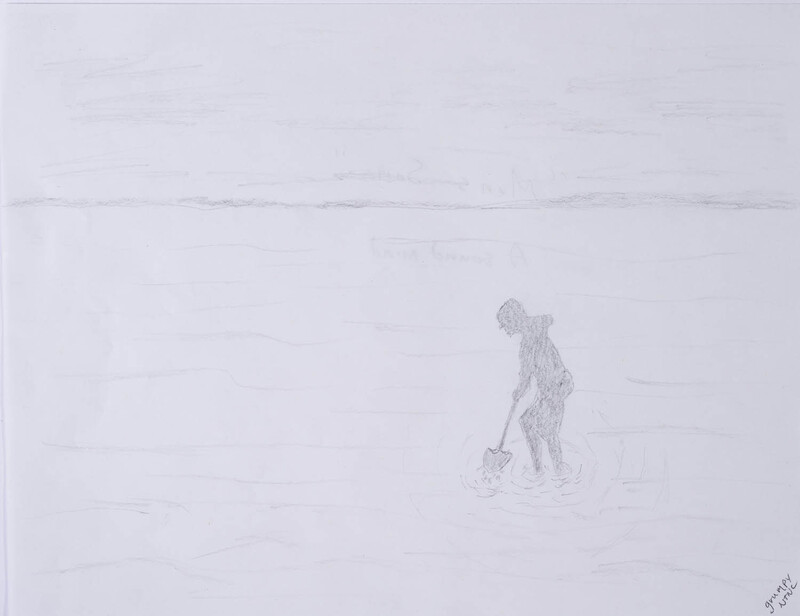

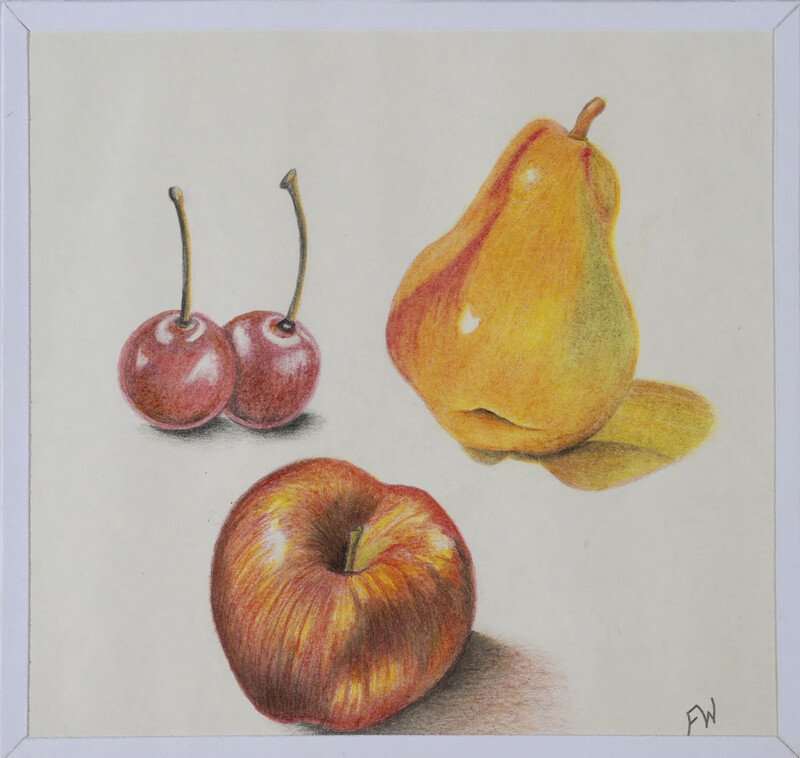

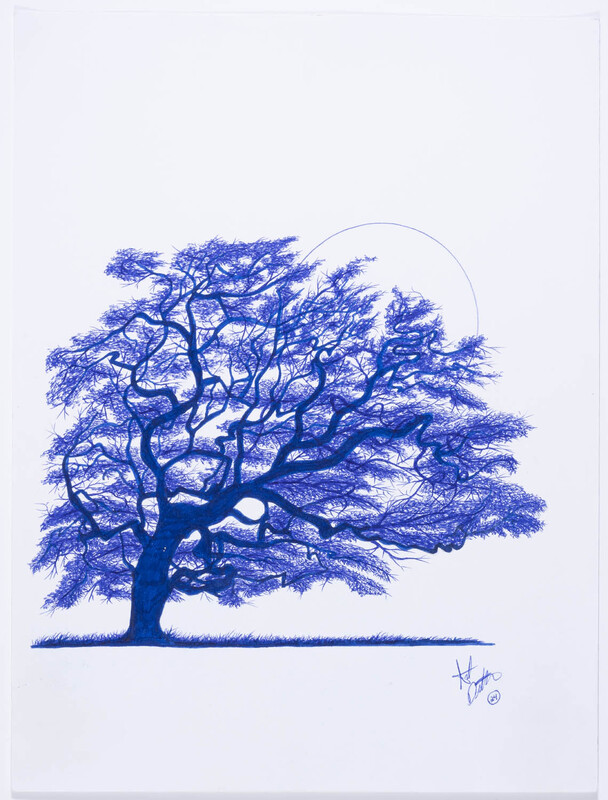

Genres of carceral art simulate commercial products that are expensive or unavailable inside and play a critical role in connecting folks inside with their families and friends. In the exhibition you will see greeting cards, crocheted stuffed animals and blankets, painted T-shirts, decorated jewelry boxes, and chess sets. Some artists work within traditional artistic genres like portraiture and landscape. You will see here, too, engagement with the work of celebrated historical practitioners like Vermeer, Van Gogh, Matisse, Picasso, and Banksy, and with visual traditions in popular culture and mass media. There are also categories of art that are more unique to prison like the “mushfakes” that cleverly utilize available and found materials to masquerade as things they are not–a spray paint can, a miniaturized motorcycle, a bottle of glue. Ballpoint pen, colored pencils, ink, and even graphite, the ubiquitous medium of sketching, perform in carceral art like nowhere else.

Many artists comment on how making art helps them cope with the oppressive conditions inside prison. Janie Paul, a free world artist and co-founder of the PCAP Annual Exhibition, observes how creative processes give incarcerated artists vital agency as active subjects engaged in assertive meaning-making. Artists establish intimate, absorptive, interactive relationships during the time spent making an artwork, assessing and recalibrating the evolving composition with each new sitting. But they also learn to live with loss, for while artists in the free world can assemble an archive and keep track of the artwork they have made across a career, incarcerated artists are obligated to send their art out of prison upon completion, without immediate access to photography to create a record of their work. In this regard, the PCAP exhibition operates as a kind of archive for artists who have exhibited over the years, with high resolution photographs, information about medium and measurements, and artist statements.

By: Megan Holmes