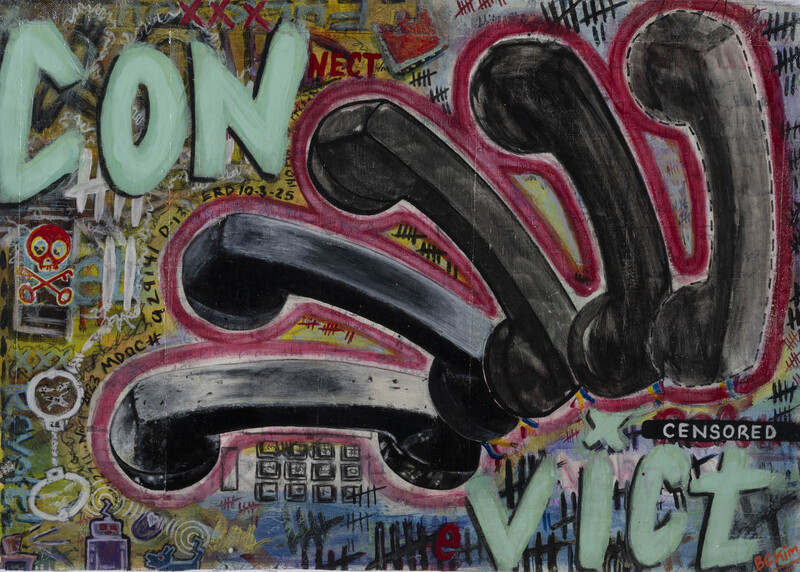

Connection

Prisons violate relationships in two key ways. First, they strain and sometimes sever ties between incarcerated individuals and their loved ones. Many artists in the Upper Peninsula, for instance, describe the arduous and prohibitive experience of receiving visits from family members who live eight to ten hours away in Wayne or Washtenaw County. They also share how the invasive security procedures—such as pat-downs—discourage visits, making it even harder for incarcerated people and their loved ones to maintain connections with one another throughout the course of one’s confinement.

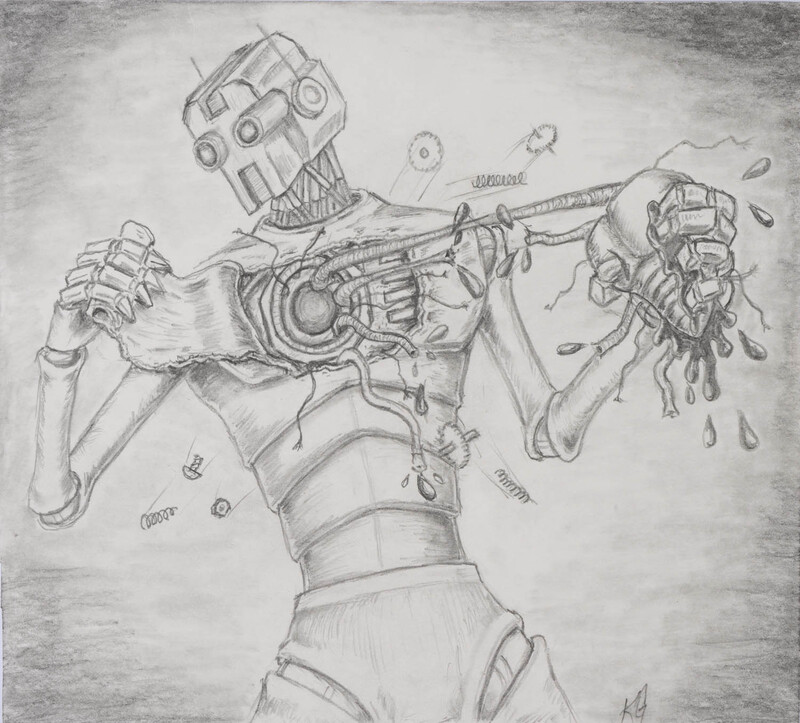

Second, prisons disturb the incarcerated person’s ability to relate to themselves. Artists speak to the ways in which the dehumanizing conditions of their confinement often warp their senses of self. In prison, they are reduced to their inmate numbers while the most basic of human intimacies and experiences like hugs, laughter, singing, and sex are turned into citable, criminal offenses. These activities which we take so much for granted as a basic part of our humanity in the free world—our capacities to connect with ourselves and with others—are punishable in prison.

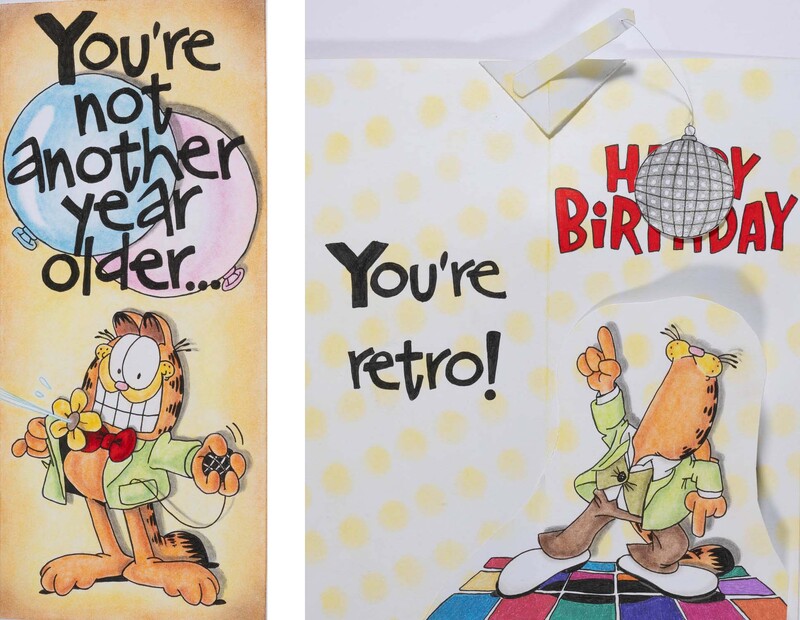

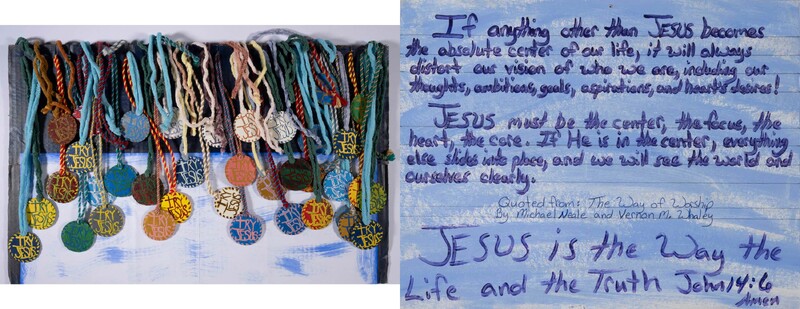

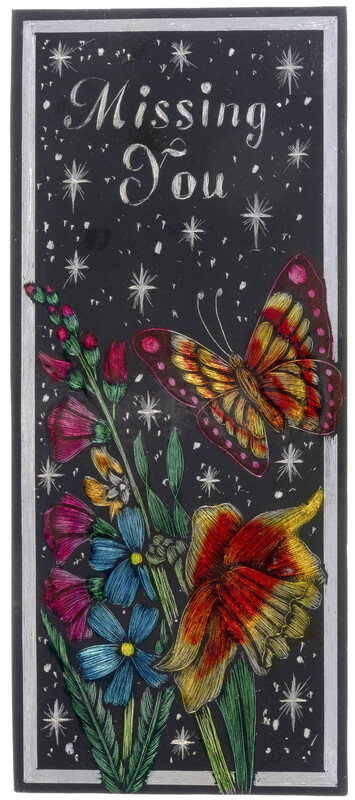

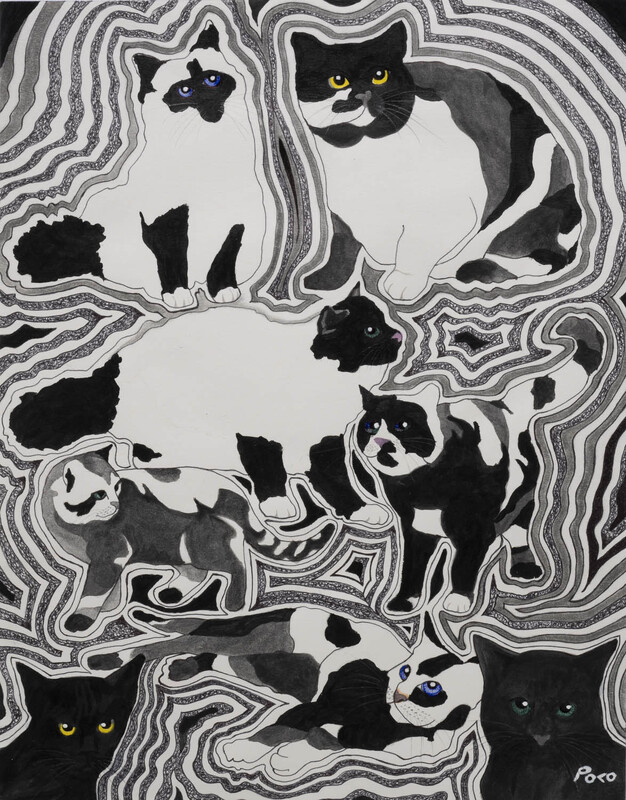

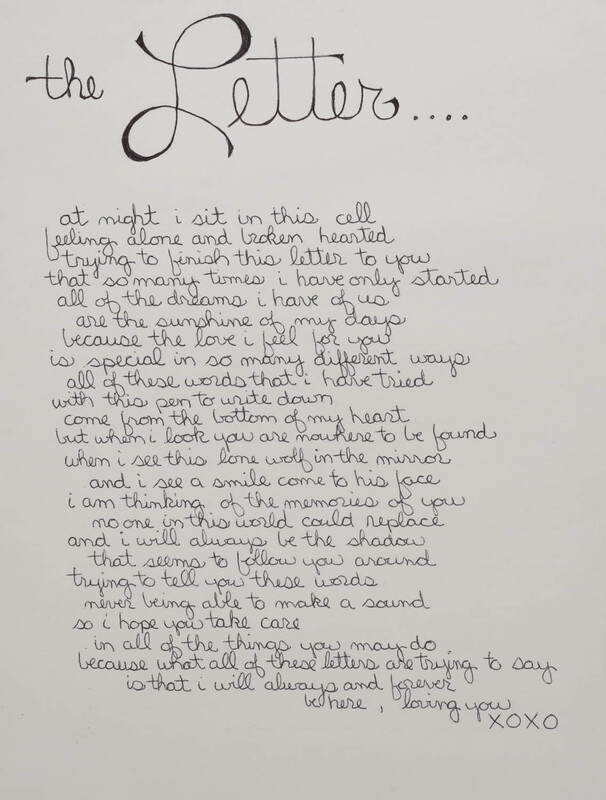

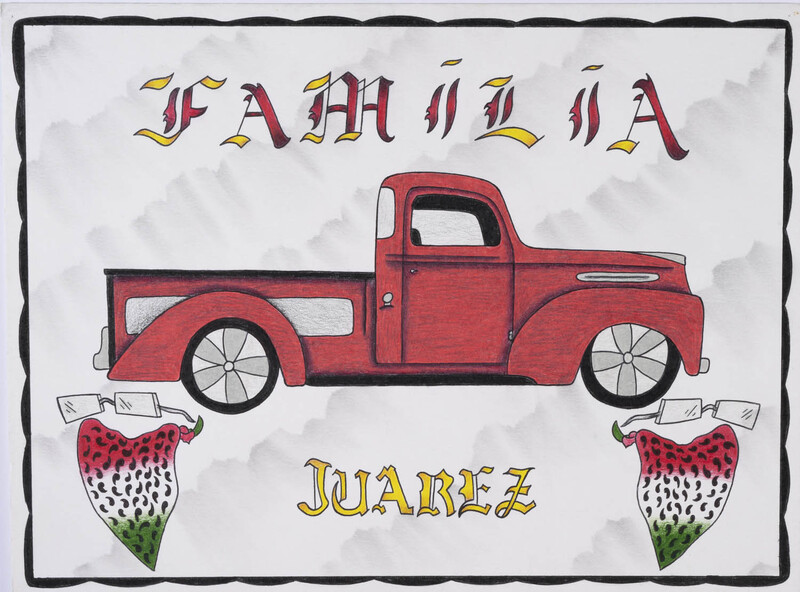

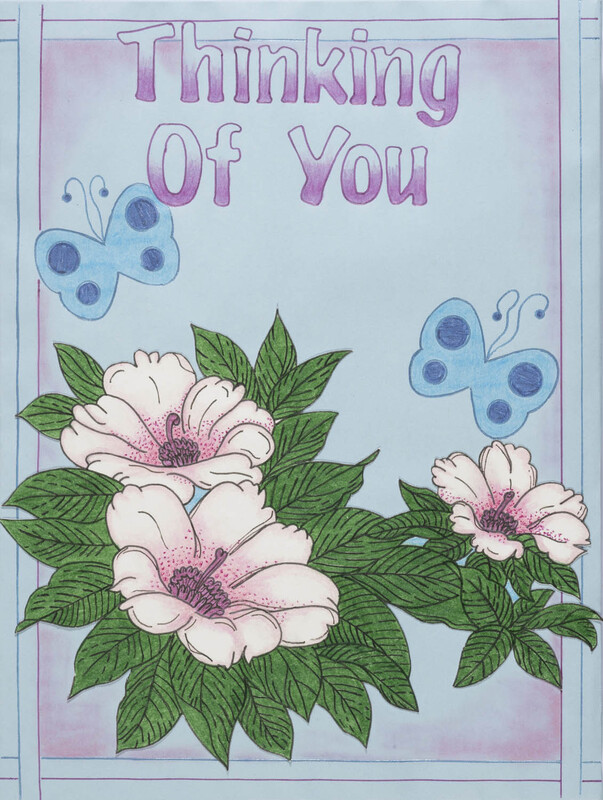

Within this context, art becomes a powerful tool for connection. Greeting cards, like those created by artists like Jimi and A.B.V.O.G., help people in prison maintain bonds with their loved ones in the free world, allowing them to participate in and contribute to important life events like birthdays, holidays, and graduations despite their physical absence. These homemade greeting cards are one of the few customizable physical objects, alongside forms of correspondence like written letters, that people in prison can send to their loved ones as tokens of affection. They are the clearest example of art as a tool for connecting to and staying connected with others.

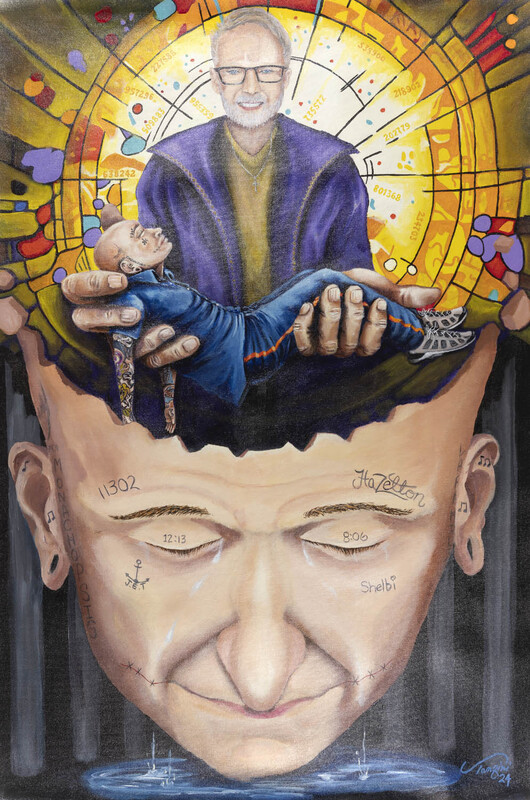

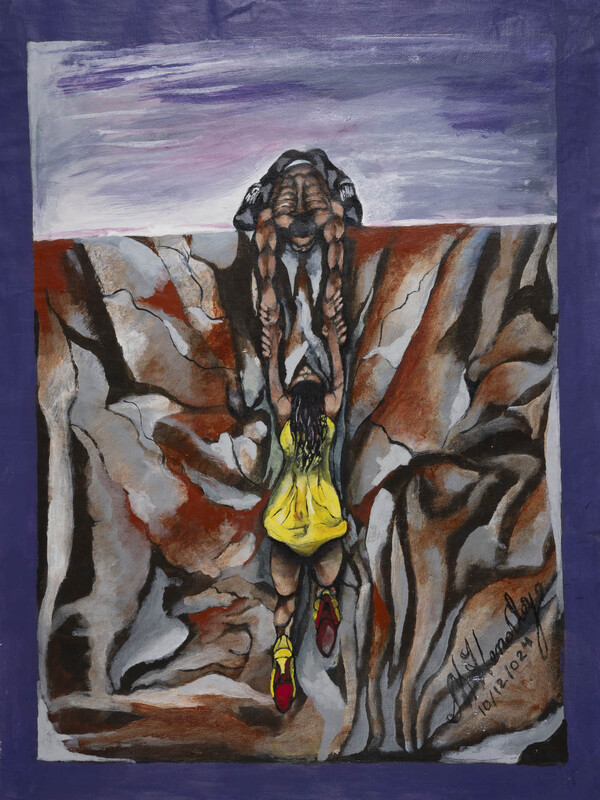

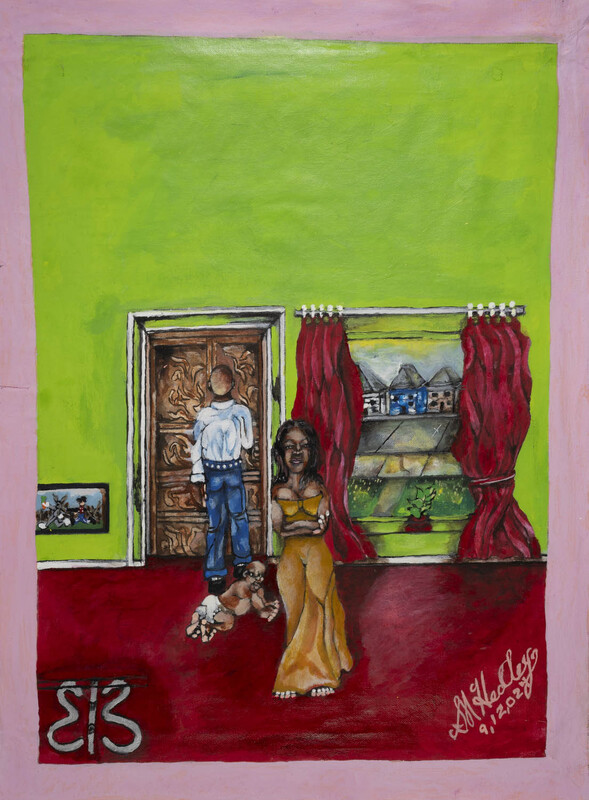

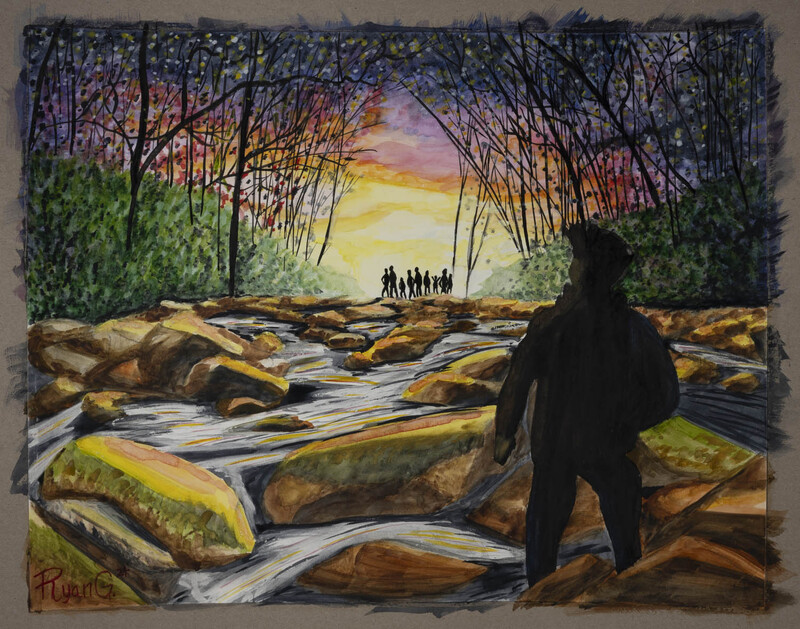

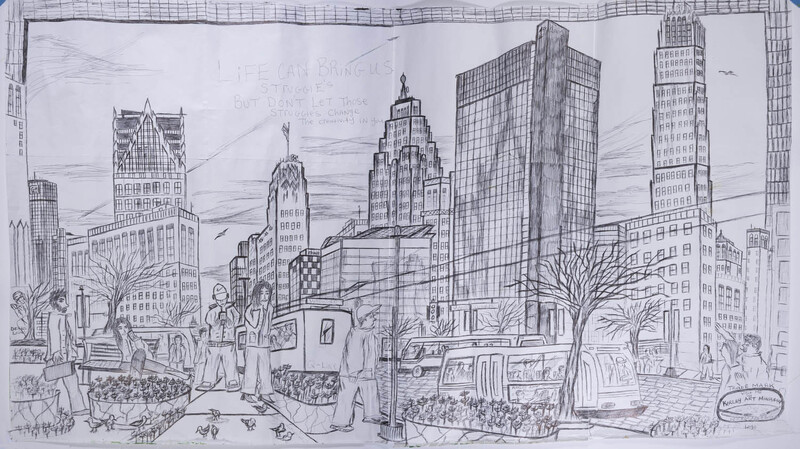

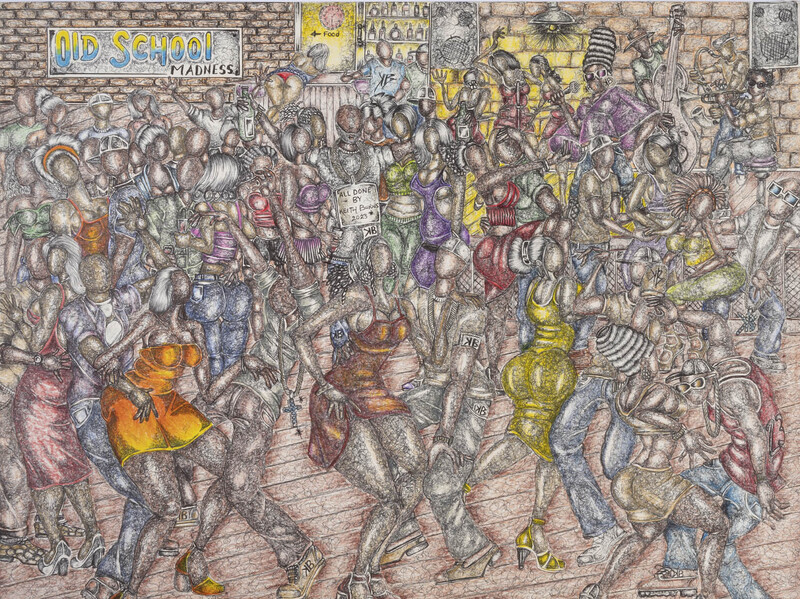

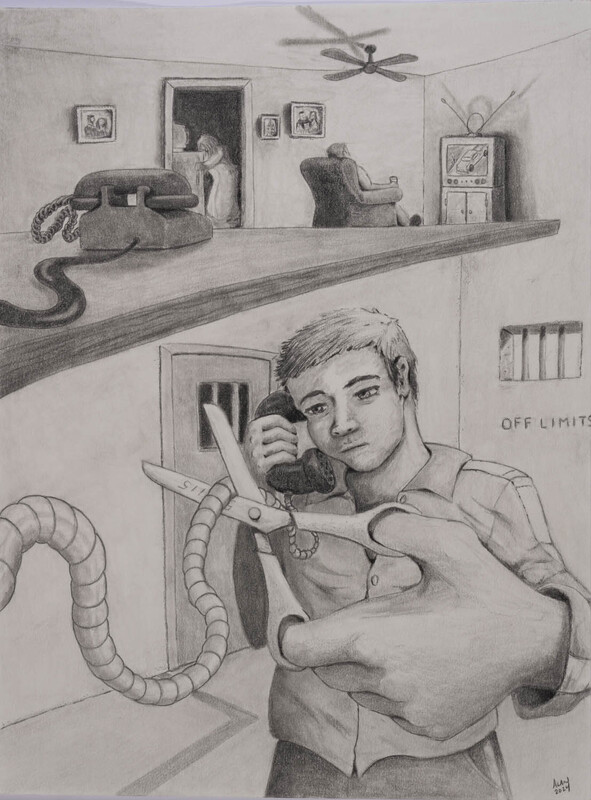

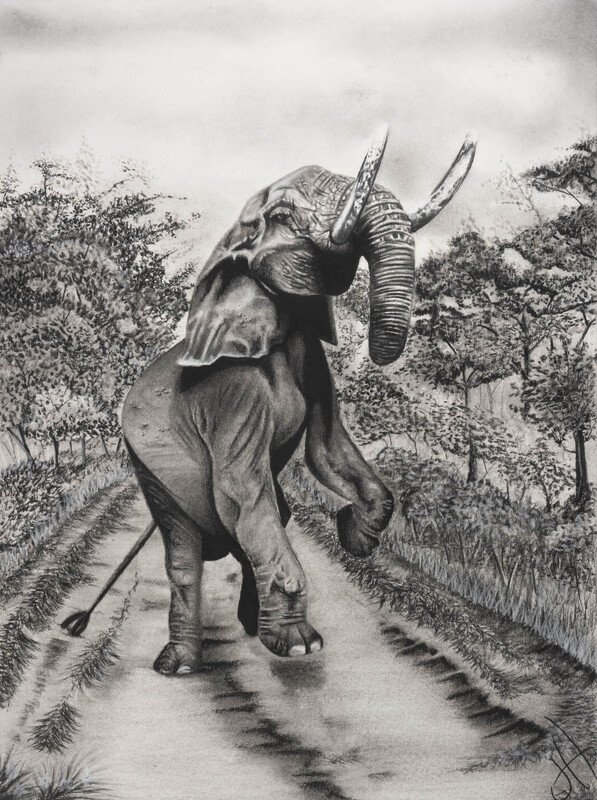

Art can also represent prison’s effect on relationships. It may serve as a means to depict the disconnection that prisons cause, as in Alan Trowbridge’s piece Untitled One, and Missed Memories by an anonymous artist at FCI Milan. It can also symbolize and memorialize the camaraderie that emerges among incarcerated people, as it is in Frederico Cruz’s We’ll Finish Together. This piece is an important counterpoint both to the isolation imposed by the prison system and how people in the free world might imagine what relationships in prison look like in the first place.

By: Vitalis Im